Appearance and reality are not the same. If I take a photo of the cup next to me, that image may capture the physical features of the cup and surrounding scene, but in many ways it fails to reflect what it’s like for me to see the cup. Vision is dynamic and temporally extended. My experience of the cup is not exhausted by any momentary “snapshot” which could be captured in a static array of pixels. Still, some images come closer than others to reflecting experience.

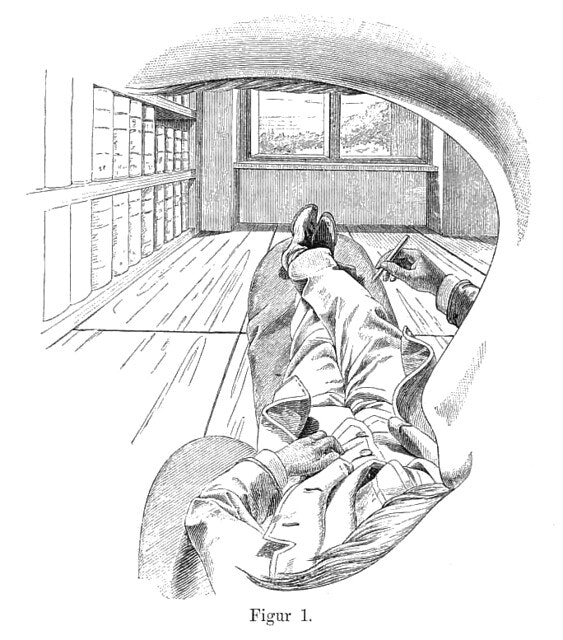

Mach’s famous 1886 self-portrait is one well-known attempt to draw what it’s like to see.

Notice the distinctive intrusion of his mustache, nose, and eyebrow ridge into the visual field. Notice also how the detail fades in the periphery. It strikes me that there’s something inconsistent about this drawing. If the attempt is to capture what’s available in the left-eye’s visual field, then Mach is right to include his mustache, nose, and eyebrow, but wrong to leave the periphery devoid of detail. True, in no single glance do you take in that peripheral detail — but the mustache, nose, and eyebrow are just as much in his periphery and only come into view with eye movements to the right. If the attempt is to capture what’s seen with a fixed eye, then Mach is right to leave out the detail in the periphery, but wrong to include his facial features. (And, Mach has probably included far too much detail in most of the frame, as only a small patch at the centre of the visual field really involved detailed resolution.)

I stumbled upon this wonderful little collection a few days ago. It looks to be the work of some art students duplicating Mach’s approach.

The above picture, from that collection, strikes me as the most representative of what experience is actually like, at least experience when the eye is fixed. Like Mach’s image, it still strikes me as including far too much of the facial ridges. (If the link breaks, here is a low-resolution version of the picture.)

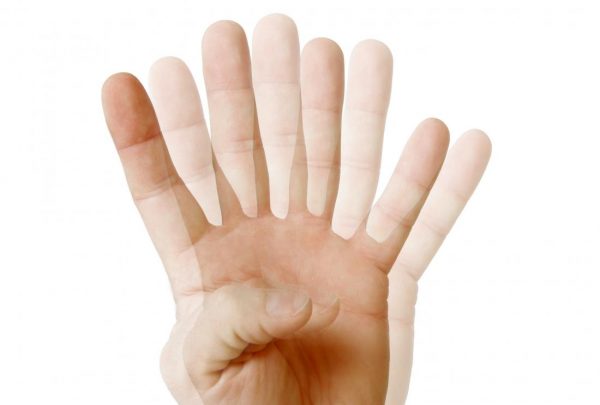

Things get more interesting when you try to depict not just what normal vision is like, but what abnormal, or purely “internal” visual phenomena are like. Consider, for example, what it’s like to see double (usually easy induced by “crossing” your eyes):

I just grabbed this image off a random website (it’s here as well). Still, I think it’s fairly accurate as to what it’s like to see your hand while crossing your eyes.

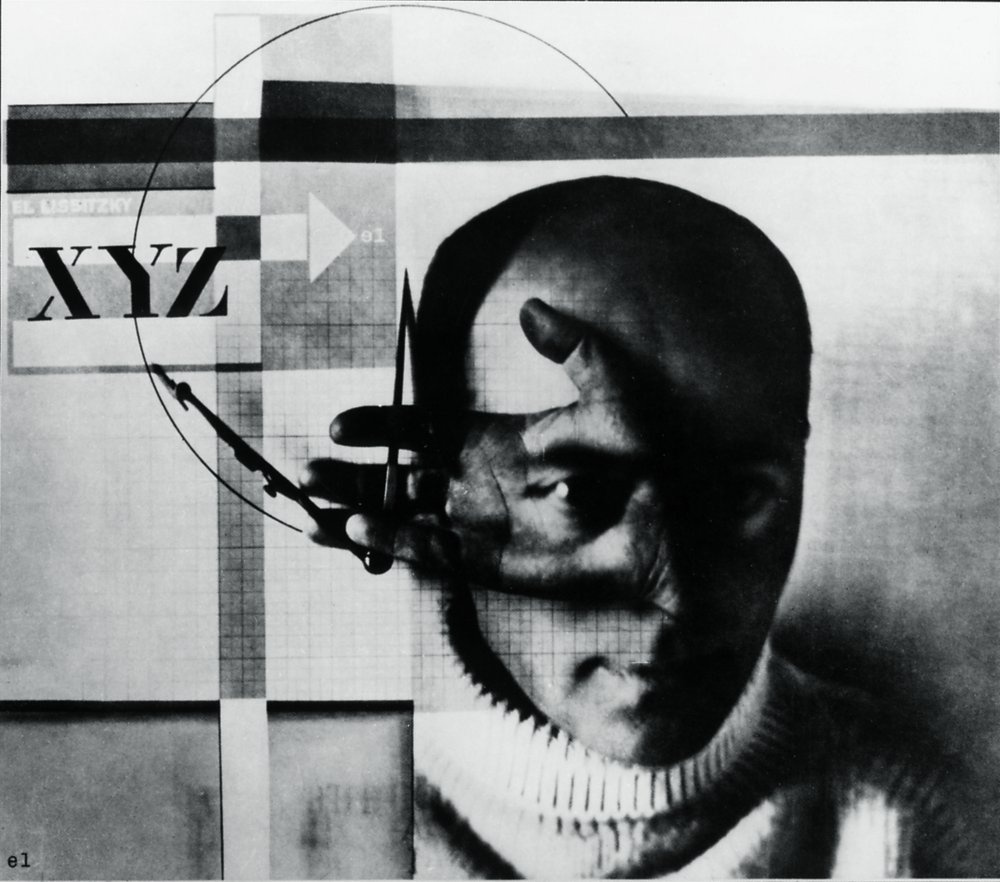

This famous self-portrait by El Lissitzky captures the effect as well.

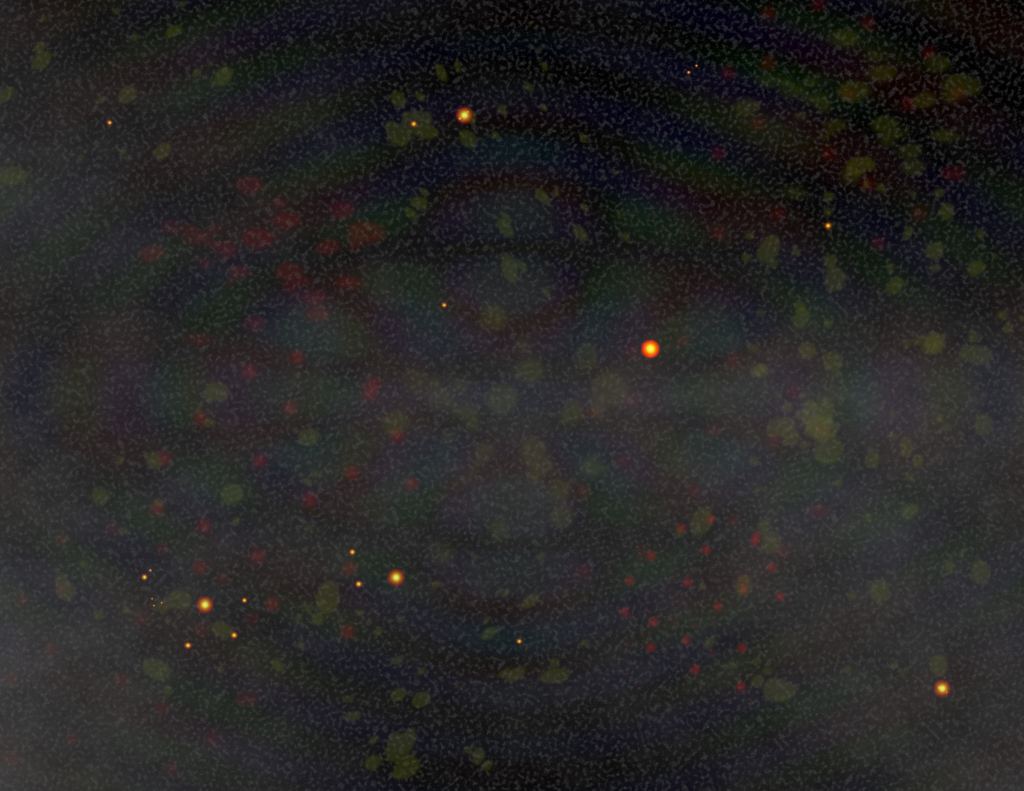

Another interesting phenomena is brain gray (aka eigengrau) or what you visually experience when you close your eyes.

The above is my attempt to reproduce what I see when I close my eyes. This image is rather muted. Many days I have much more vivid spots, streams, and clouds of vivid reds, yellows, blues, and greens. Often these form radical lines, and much of this “light show” persists in my normal visual field all day long, even with eyes open in daylight.

Somewhat related, at least in terms of appearance, is this image produced by one of my students:

As he describes it, “I used effects [in paint.net] that I think are similar to what the visual system might use to generate the imagery such as adding noise, structuring that noise, and sharpening it. I see very similar images when I’m about to fall asleep but it’s inherently dynamic which is hard to capture in an image.” My own hypnagogic imagery is often much more coherent and structured (e.g., faces or whole objects), but I certainly have phenomena like what’s depicted in the image in many cases.

Scintillating scotomas are another interesting “internal” visual phenomena. Here are some artist depictions from the wikipedia page:

By Greensburger, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7399912

By Kronos – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15179613

Here is an image I made based on my own experience with a scintillating scotoma:

Finally, I wanted to mention the Extreme Imagination Exhibition (Extreme Imagination: Inside the Mind’s Eye) from my friends at the Centre for the Study of Perceptual Experience (University of Glasgow). Here is how they describe their project:

A small percentage of the population do not experience mental imagery (they have aphantasia); another minority experience particularly vivid mental imagery (they have hyperphantasia). Both groups include artists, writers, and designers. Our exhibition presents their work, inviting us to consider the role of mental imagery in making art. How can someone make anything without being able to imagine what they want it to look like? Is there a distinctly hyperphantasic kind of art? As far as we are aware, this is the first exhibition to reflect on these questions – perhaps because the centrality of mental imagery to art-making has previously been assumed.

I encourage you to check out their online exhibition!